jealous of a dog.

There have been mornings in my life — more often during the eating disorder itself, but sometimes even now in recovery — when I’ve felt so disgusted with myself (usually in relation to something I “shouldn’t have” eaten the night before) that I couldn’t even bear to be seen in the world.

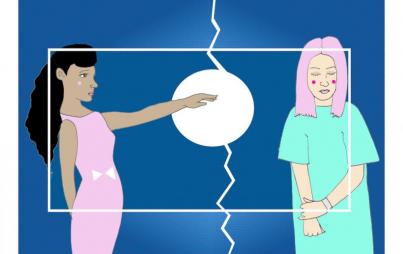

With all of the misconceptions about eating disorders abound, one sticks out the most, especially in regards to restriction: the pervasive, frustrating myth that eating disorders are diets.

Similar to when people believe depression to be “a touch of sadness” or obsessive-compulsive disorder to be “a privy to neatness,” reducing the psychological hell of an eating disorder to a commonplace, widespread activity such as dieting is a slap in the face.

And I get it. At face value, restrictive eating disorders do look like diets. But although diets also involve traveling through the depths of an inferno known as Self-Hate, eating disorders invoke a special kind of crazy-making that needs to be described.

But before I get started, I want to point out that I’m writing this article specifically from my own experience to give a more in-depth, authentic look at the eating disordered mind. Unfortunately, my positionality — that of the thin, white, able-bodied, cisgender, middle-class, educated, conventionally attractive woman with an anorexia nervosa diagnosis (although, for me, this showed up atypically) — is the one most often given in eating disorder stories, so I can only offer so much.

So please (please) don’t stop here. Look into the stories being told at The Body Is Not an Apology and Thick Dumpling Skin, through Nalgona Positivity Pride and Trans Folx Fighting Eating Disorders. Buy copies of Not All Black Girls Know How to Eat and A Hunger So Wide and So Deep. Don’t let me be your authority on All Things Eating Disorder. I’m only the authority on myself.

This story is only mine.

But here it is.

Here are five ways that my eating disorder showed up that leaves no room for debate about whether or not it’s a diet, because it’s oh-so-clearly a mental illness:

1. I’ve Been Jealous of a Dog

I can’t believe I’m publishing this (let alone starting with this), but here goes nothing.

One afternoon, early on in my recovery process, I took my then-girlfriend for a walk in Atlanta’s city park. I lived in Atlanta for three years, and I can’t say that I miss too much about it (uh, hence my leaving), but the price of living was cheaper, the restaurant culture was good, and Piedmont Park, though manmade, is amazing.

As we passed the playground where children were swinging, sliding, and hide-and-seeking, there was a woman standing by a water fountain, her dog on a leash. I can’t remember now if it was a poodle or a greyhound, but it was a naturally thin breed.

I stared at it for a minute, trying to collect the absurd pool of thoughts forming in my mind — and then I had to sit down because I felt like I was going to cry.

I was jealous of the dog.

“That dog gets to be so thin,” I tried to explain, tearfully, to my partner, “and it doesn’t even have to try. I’ll never be that thin.”

And if this was a one-time, never-again-to-be-repeated kind of scenario, maybe I’d chalk it up to having been particularly hormonal and sensitive at the start of recovery, but it’s happened more than once.

Maybe it’s not always a dog. Maybe sometimes it’s been a young child, a prepubescent girl whose body has yet to grow and curve. I would think, “If only I knew then that I could get fat, I could have stopped it before it started.” Even sometimes still, it’s been a baby, throwing me into a spiral about what, ultimately, my lowest weight in life really was.

And even as I type this, I know how absolutely absurd this all sounds. But that’s the thing about an eating disorder and the way that it affects your brain. It’s not about being casually, off-handedly jealous of the woman who sits down next to you in yoga class (yes, I admit, that happens to me still) — it’s about being thrown into remorse over a truly impossible comparison.

2. I’ve Called Out of Work Because I Felt Too Hideous to Be Seen in Public

Let me be clear again: I’m a thin, white, able-bodied, cisgender woman who presents as feminine. By all of those virtues, I fit into society’s bullshit beauty standards. On top of that, I’m also otherwise more or less conventionally attractive (and I only say “more or less” because I’m moderately tattooed, which, although becoming more acceptable and desirable by society’s standards, still isn’t exactly “conventional”).

That is to say, aside from the patriarchal shit that all of us get from the pressures of the beauty myth, I’m privileged in almost every single way, which means that I get a lot less shit from society — in terms of everything, but also, more specifically, in terms of beauty standards — than most people.

In other words: I have absolutely no reason whatsoever to believe myself to be monstrous.

Aside from, you know, this whole eating disorder thing that (literally) eats my brain.

And it would feel incredibly, embarrassingly pathetic — if it weren’t for how real it can feel.

There have been mornings in my life — more often during the eating disorder itself, but sometimes even now in recovery — when I’ve felt so disgusted with myself (usually in relation to something I “shouldn’t have” eaten the night before) that I couldn’t even bear to be seen in the world. I’ve been ridiculously embarrassed to go outside and be seen in the light of day, thinking that no one should be forced to gaze upon my hideous body.

Sometimes this manifests in other ways (like not wanting to put on clothes, but more on that later), but it tends to result similarly: an “I’m too sick to come in” call, and a day spent wallowing in my own self-pity.

And while I think that mental health days are necessary for self-care and that a well-placed, much-needed pity party can push us out of our despair, when they become a possible part of day-to-day life, there’s a serious problem, especially when the core of the issue is entirely imagined.

3. I’ve Suddenly Felt Suffocated by Clothes

I don’t wear turtlenecks because, one, I think they look weird (no offense, y’all) and two, they make me uncomfortable. I wear skinny jeans, though, despite the impossibility of peeling them off (I’ve broken nails trying to get them up and over my butt), because I love them.

But I’m not talking about clothes that are actually arguably suffocating.

I mean, like, sweatpants.

My partner and I are in a long-distance relationship — one that started because we’d known each other chiefly online (thanks, Internet feminism!) for years. When romantic interest developed, it only made sense that I’d hop on a plane to visit the (So Not The) Best Coast to see what kind of flame we could ignite face-to-face.

And then, on my last full day there, when he’d planned all sorts of beautiful adventures in San Francisco, a city I’d never visited, suddenly, it hit. I had to take my clothes off.

It sounds amusing, especially considering the context. I think that in many situations, a person would be pumped if a person they had a romantic interest in was so overcome by emotion that they just had to be naked — but this situation isn’t one of them.

It starts the same way that many days do: with an unshakeable discomfort in being in my own skin. I wake up feeling too… something. Like I take up too much space. And then, upon dressing, the emotion escalates — because I suddenly feel like I’m taking up much more space in my clothes than I usually do.

My mind starts to race: What did I eat last night? Is it possible to gain 10 pounds overnight? Am I just bloated? What’s wrong with me? What happened to me? Why do I feel so disgusting? Is that all of the food I’ve eaten in the past week that I feel, swimming around in my intestines? How can I get it out? How can I get it out? How can I get it out?

And then, all at once, clothes feel like they’re choking me, like they’re going to compress me until I burst.

And I have to remove them all.

In the case of that day with my partner, I lucked out: He didn’t think I was weird when I told him what I needed, and he let me lie down and be held. He didn’t force me to get dressed or go anywhere. When I started to try to explain, he told me it was OK, that he understood — to some extent — what was happening.

But sometimes, there isn’t anyone there that can calm me down. Sometimes the feeling lasts all day.

4. I’ve Started Hallucinating

For me, the scariest part of my eating disorder wasn’t near-blackouts. It wasn’t the mortifying calorie obsession that had me constantly doing math I didn’t even know I had the capability to do without a calculator. It wasn’t even when my body started rejecting the restriction and would force me into uncontrollable bingeing (and the subsequent uncontrollable crying fits).

It was when I started seeing things.

We can probably chalk this one up to malnourishment of the brain, but I eventually developed a terrifying combination of hallucinations and paranoia that, honestly, became my first inkling that something was actually really wrong.

And it always happened the same way: I’d be driving, minding my own business, when suddenly, out of the corner of my eye, I’d see a dark figure standing on the edge of the road, starting to cross. Terrified I was about to hit someone, I’d panic, and I’d search my rear-view mirror in horror, trying to place where they were — but I could never find them.

That is, until the same dark figure again appeared at the corner of my eye.

After a while, unsurprisingly, this developed into a paranoia that I couldn’t shake. Gripping the steering wheel, breathing shallowly, constantly reassessing my peripheral vision — it became impossible for me to drive without fear.

I was worried about what was happening to my eyes...until I realized that it wasn’t my vision that was the problem. I was hungry.

More to the point, I was starving. And that’s why my mind was playing tricks on me.

5. I’ve Screamed, Cried, and Gotten into Fights Over Food

There’s this cute shirt I’ve seen being sold all over the Internet that reads “I’m Sorry for What I Said When I Was Hungry.” Here’s an example. It’s a joke shirt about how people get quote-unquote “hangry” (and trust me, that’s definitely a thing).

But every time I see people post this T-shirt (or even, honestly, talk about their “hanger”), I want to say, “Stop. You have absolutely no idea.”

Because it can get bad.

And I’m not talking “I’m hungry, so I’m cranky, and I snapped at my partner a little bit or was an annoying person to be around all night until I finally had some pizza.” I’m talking straight up making a scene.

The night that I was finally confronted (or, at least, confronted in a way that got through to me) about my eating disorder has been recounted so many times, I won’t do it again here. But this wasn’t the only time that a food-related incident had me, as I like to call (thanks, T. Swift), “screaming, crying, perfect storms.”

“I can make all the tables turn,” alright — and in a way that puts all of the blame on the other person, leaving them flabbergasted trying to figure out where everything went wrong.

Whether it was my mom, surprising me with take-out pizza, or my ex-girlfriend’s accidental supposed non-sequitur between “My pants are so loose” and “What do you want for dinner,” or a partner offering to take me out on a date to my favorite restaurant, I’ve fallen apart over the mere mention of food — to an embarrassing level of passion.

You don’t know hangry until you’re hiccupping between sobs, trying to explain to someone that you love that you’re sorry for yelling, but food is just so damn scary.

In her brilliant spoken word poem, “When the Fat Girl Gets Skinny” (no, seriously, this performance should be required watching for anyone who’s ever had an eating disorder or had to deal with someone who has), Blythe Baird says, “This was the year of eating when I was hungry without punishing myself / And I know it sounds ridiculous, but that shit is hard.”

And sometimes, talking about food without screaming is hard. And sometimes, coming to the realization that your brain is eating itself is hard. Just like remembering that no, you cannot gain 10 pounds overnight is hard, and like recognizing that your body isn’t monstrous is hard, and unlearning ridiculous jealousy is hard.

Because eating disorders are hard. Because mental illness is hard.

And it’s about time that we recognize that that’s what eating disorders are.